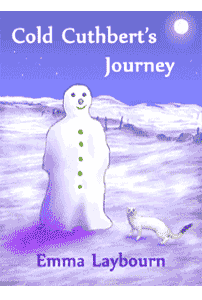

COLD CUTHBERT'S JOURNEY

by Emma Laybourn

Chapter One

"He's the most wonderful snowman in the world!" announced Lily.

Owen wasn't too sure about that. But he was certainly a very fine snowman. He had taken them all afternoon to build.

"He just needs a face," said Lily. "He can't see yet, or hear."

"He won't-" Owen stopped. "All right," he told his little sister. "We can give him stones for eyes."

"No, no, not stones! Wait a minute!" Lily ran into the house.

Owen stamped his frozen feet and reached up to pat the snowman's head. The shadowed side of it was blue, while the other, facing the low sun, glowed coral pink - almost as rosy as Owen's cheeks, which were red with cold and effort.

The snowman was very big: the biggest that Owen, in all his nine years, had ever managed to build. But then the snow this winter had been better than ever before.

Better for building snowmen, that is. It was wonderful for snowballs and snow-fights and fun. It was not so good for Owen's dad, who was a farmer.

The snow came up to the tops of the dry-stone walls that edged the fields. It wiped out the farm tracks and threatened to smother the sheep. Dad had spent all day rescuing snowed-under sheep from the deep drifts in every dip and gully.

Owen could see Dad now, trudging slowly across the field towards him.

"Did you find them all?" he called out.

"Nearly." Dad looked tired. He was snowy up to his waist. "I should go and look again."

"No, you shouldn't! It's half past three, and the sun's almost setting. And anyway, it's Christmas Eve," Owen pointed out. "Stay here. You can help us finish our snowman."

"He looks like I feel," said Dad. "A handsome chap, but chilly. Where's his face?"

"Here!" Lily came running out of the farmhouse. "I've got shells for his ears," she panted, "and conkers for his eyes."

They were Owen's conkers, that he'd carefully collected in the autumn; but he didn't mind. He helped Lily put them in position.

With his shiny chestnut eyes, the snowman suddenly looked much more like a person.

"Here's a turnip for his nose," said Mum, who had followed Lily out, "seeing as I've got no carrots. And how about this spring onion for his mouth?"

"Brussels sprouts for buttons," said Lily, pressing them onto the snowman's broad stomach.

"Best use for them," muttered Owen.

"He looks a bit chilly. Shall I get him an old hat and scarf?" asked Mum; but Lily protested.

"No, no, no! He's meant to be chilly. He mustn't get too warm! We don't want him to melt!"

"He won't-" began Owen, and then stopped himself again. "Okay. No hat or scarf. All our snowman needs now is a name."

"Frosty," suggested Mum.

"Snowy," said Dad.

"Sparkle!" cried Lily.

Owen pulled a face. "No, he's not a Sparkle. He's a... Cuthbert."

"Cuthbert? I don't think Mr Gilpin would be too pleased," said Mum.

Mr Gilpin was the minister at the village church. It was called Saint Cuthbert's church, and inside there was a wooden statue of Saint Cuthbert, looking rather gloomy. Not surprising, said Dad, when he had Mr Gilpin for company. Mum said Saint Cuthbert just didn't care for crowds.

The children were always trying to cheer Saint Cuthbert up. But when Lily dangled daisy chains around him in the spring, Mr Gilpin frowned. When Owen hung a string of onions round his neck at harvest festival, Mr Gilpin got quite stern.

And when they both decorated him with tinsel just last week, Mr Gilpin shouted.

Mr Gilpin took Cuthbert very seriously. So he would not like the idea of a snowman with a turnip nose being called after his saint.

"Mr Gilpin won't know," said Owen. "We won't tell him."

"Anyway, our snowman is Cold Cuthbert," said Lily. "Not Saint Cuthbert."

"Cold Cuthbert is a grand big snowman," Mum assured her. "But it really is time to come inside now! It's chilling down fast out here."

Dad looked out across the rosy, snowy fields. Owen knew that he was worrying about his sheep.

"It's not going to snow any more, Dad," he said. "Look how clear the sky is! The sheep will be okay tonight."

"It's not the snow I'm worried about," Dad answered. "It's the temperature."

"Will Cold Cuthbert still be here tomorrow?" asked Lily, swinging her arms to keep warm.

"You bet. He'll be Colder Cuthbert by the morning. He won't melt, that's for sure."

"But will he stay here? He might walk away, like the one in the cartoon!"

"He won't-" began Owen, and then stopped, for a third time.

"He might," said Mum. "But snowmen can only walk when it is very, very cold and very, very still indeed. He might just have moved a yard or two by morning."

"I'll come out first thing and check!" declared Lily.

"But right now we're going inside before we freeze into snowmen ourselves. I'm going to make toasted teacakes and hot chocolate. Any takers?"

"Me!" yelled Lily, and they all hurried into the warm, bright kitchen of the farmhouse, leaving Cold Cuthbert standing like a lonely pillar in the field.

Chapter Two

As soon as Owen pressed the conkers into Cold Cuthbert's snowy face, the snowman found that he could see.

And as soon as Lily fixed the shells on to his round white head, he found that he could hear.

He watched the family with his shiny chestnut eyes and listened to them talk. So now he knew he was a snowman called Cold Cuthbert.

He knew that if he got too warm, he might melt.

He knew that Mr Gilpin - whoever he was- would not like him.

And, most importantly of all, he knew that if it grew very, very cold and still indeed, he would be able to walk. The children's Mum had said that; so it must be true.

Cold Cuthbert tried to stretch his snowy legs. They wouldn't move. Obviously it wasn't cold enough.

In fact, in his opinion, it wasn't really cold at all. From where he stood, he could feel the warmth of the farmhouse; while to the west, the last rays of the sun seemed to the snowman to burn as hot as an electric fire.

He gazed at the sky, which glowed like a distant, golden shore. He could tell that it was getting colder. So he watched and listened, waiting.

He heard the rooks joking with each other as they settled in the oak trees for the evening. He heard the sheep baa-ing their good-nights across the fields. He heard an owl hoot a warning from the little wood as it set out to hunt.

He heard the robin piping in the hedge, practising his song for morning. And from inside the house, he heard more singing; this time, from the children.

Gradually all the sounds grew quiet. The golden shore along the sky turned red, then mauve, then grey; then slowly deepened into inky blue.

Now he was growing colder. He felt the strength of ice hardening within his body.

Was he cold enough yet to move? He tried to stretch a leg- and failed, again.

So Cold Cuthbert waited patiently. He watched the moon rise, like a perfect snowball thrown up into the sky and unwilling to come down. A thousand stars began to glitter; while the snow, luminous in the moonlight, glittered back.

Then Cuthbert noticed something by his feet. It was the same colour as the snow, and it jumped and twirled and pounced on its own dark moon-shadow.

The something stopped and looked up at the snowman with black beady eyes.

"Who are you, and what are you doing here?" it asked.

Cuthbert discovered that although he could not move his legs, he could now move his mouth and speak.

"I am Cold Cuthbert, and I am waiting for it to be cold enough for me to walk," he whispered.

"Hah!" The creature sat up. It had a long, slender, sinuous body. "I am a stoat. Or rather, at this time of year, with my fine white winter coat, I am Lady Ermine."

"Happy to meet you, Ermine," answered Cuthbert. "Why are you jumping around like that?"

"I'm playing," she said. "Do you want to play?"

"How do you play?"

"Like this!" Ermine began to tumble and turn somersaults and chase her tail.

"When it is cold enough and still enough, I'll play with you," the snowman promised. He was not sure if it ever would become still enough, with Ermine leaping round like that; but he was too polite to say so. Instead, he just kept waiting.

Inside the farmhouse, the last light went out. In the fields, the sheep were silent. The owl paused in her hunting to rest.

And Ermine tired of playing on her own and curled up in a furry ball to take a nap.

The only thing that moved now was the moon, as it slowly, slowly crept across the black bowl of the sky.

Surely now it was still enough? thought Cuthbert. Surely it was cold enough?

For he was longing to take his first step.

Chapter Three

Inside the farmhouse, Lily woke.

Had Cold Cuthbert begun to walk yet? For a moment she thought of getting up to see.

Then she remembered what Mum had said to her as she tucked her into bed:

"No getting up in the night, now, Lily. You don't want to disturb Santa Claus's reindeer, do you? You might frighten them away."

Lily had promised. Now she lay and listened for the sound of sleigh-bells, or the clatter of reindeer hooves up on the roof; but she heard only silence. A minute later she was asleep again.

As she fell asleep, Owen's eyes opened. The moonlight glimmered through his curtain. He remembered that it was Christmas Eve; and he lay and listened too.

He felt the stillness of the night, which was the greatest stillness he had ever felt. He listened to the silence, which was the deepest and most peaceful silence he had ever known.

He thought of getting up to look out of the window at the moonlight shining on the snow. But when he poked his nose out from his covers, he realised that it was extremely cold. He burrowed back down into the warm den beneath his quilt, and fell asleep again.

So neither Owen nor Lily saw the moment when Cold Cuthbert moved.

They did not see him take his first, slow, gliding step. They did not see the smile that spread across his mouth as he took another gliding step, and then another.

Ermine woke up and bounded after him.

"You're walking!" she exclaimed.

"Well, of course I am," said Cuthbert gladly. "Didn't they tell me that I would?"

Ermine shivered. "This is the coldest yet," she said.

But Cuthbert felt his energy increase with every drop in temperature. As he walked away from the farmhouse to the chill of the open fields, he moved faster. So did Ermine; though in her case, it was in order to stay warm.

Because the snow had covered the stone walls, he could cross them easily. He stood and marvelled at the huge, still space of moonlit pasture spread before him, like a present just unwrapped.

"I have been given all this world to walk through!" he declared in awe.

With Ermine bounding alongside him, he half-glided and half-strode across the icy fields. Being made of the same snow as he was walking on, he did not sink. The silent, waiting land around him filled him with tremendous joy.

Soon they had left the farmhouse far behind and reached the little wood.

"What is this?" asked Cuthbert.

"This is the deep dark forest," Ermine said. Bravely Cuthbert stepped beneath the oak trees, far below the sleeping rooks and dozing owl. He gazed around in fascination.

Here the snow was criss-crossed with a net of shadows. The moon kept hiding. Diving through the snow, Ermine snuffled through the undergrowth for shrews or voles to eat; but they were huddled in their tiny burrows, and she came up disappointed.

Cold Cuthbert wondered at the trees. They had so very many arms and fingers which could hold onto nothing but the chilly air. And they had no legs, poor things.

"They can't walk like me," he murmured, pitying them. As he strode on, he felt a deep delight at his own strength and vigour.

At the far side of the wood, the moon shone brightly once again. Cold Cuthbert made for the highest point that he could see; a hill not far away. It was not very big, nor very steep, and with Ermine scampering beside him, he soon gained the summit.

There he stopped to gaze around in wonder.

"I can see the whole wide world," he said to Ermine, "and it is amazing!"

For under the vast, glittering arc of the sky, line upon line of snowy hills stretched away to the horizon.

The silver slopes were dotted with snow-covered farmhouses. Below him was a village, with a crooked street and a building with a tall, pointed roof. It was easy to see because it was the only roof in the entire world that was not white.

"Perhaps the snow on it has melted," murmured Cuthbert.

"Let's play now!" Ermine begged him. "You said that you would play!"

"Play what?"

"Tag!" she called, already leaping and loping away from him. "Catch me if you can!"

At first Cuthbert did not think that he had any chance of catching her. But so cold and so still was the night that he found that he could not just walk, but run. Now he could leap and lope as well as Ermine.

Laughing with pleasure, he jumped and twirled and pounced on his own shadow, and then took turns to chase her and be chased. They seemed to be the only creatures in the whole wide world that moved, as they bounded across the moon-bright snow.

"Catch me if you can!" called Cuthbert. He ran away from Ermine and plunged down the hill.

But the hill was steeper than he'd thought. He couldn't stop running, faster and faster, until he lost his footing and toppled over helplessly. Flying head over heels, he rolled all the way down to the bottom.

"Nice somersault!" cried Ermine, racing after him.

Cuthbert sat up in a snowdrift and shook each limb carefully in turn. No bits seemed to have broken off. Getting thankfully to his feet again, he stopped.

"Ermine? What was that?"

Chapter Four

"What was what?" asked Ermine. "Caught you! I win!"

"What was that noise?" Cold Cuthbert paused to listen. There it was again: a thin, faint, mewing sound.

"That? That's a lamb," said Ermine, lolloping lightly over the snowdrift. "It's down here in the snow. Born too early: dearie me!" She shook her head.

"Dearie you? What do you mean?"

"I mean here is its mother, lying dead under the snow," said Ermine, "and the lamb will be dead, too, by morning."

Cuthbert was confused. "Dead? Why?"

"With cold, of course! Babies need to be kept warm," said Ermine wisely. "This one's too big for me to warm up, though. And I'd never fit it in my den."

The lamb bleated again, plaintively. Cold Cuthbert waded through the snowdrift to look down at it.

It lay sheltered by the ewe, its mother; but its mother was cold and still. The snowman pondered this. It did not seem to make sense. Was cold not good for everybody?

"Poor thing," said Ermine. "I'm too small to help it."

"But I am large," said Cuthbert thoughtfully. "I am a grand big snowman. What can I do to help this lamb?"

"Take it somewhere warm," said Ermine, "somewhere the humans will find it and look after it. They like sheep better than stoats."

So Cuthbert bent to pick the lamb up in his snowy arms.

"No, stop!" protested Ermine. "You'll freeze it solid! Wrap it in leaves or bracken."

Cold Cuthbert dug beneath the snow and came up with a rustling armful of brown bracken. Brushing the snow from it, he wrapped it round the lamb before he picked it up again.

Then he carried his bundle out of the snowdrift and trudged back up the slope. The lamb was surprisingly heavy.

Where could he take it that was warm? He was a long way from the farm by now, and was not sure that he could carry the lamb all that distance back.

His eyes fell upon the village down below. There would certainly be humans there; and that tall, pointed building looked as if it might be warm.

So across the snowy fields walked Cuthbert, carefully carrying the lamb.

As he walked, he realised that the light was slowly changing. The moon was growing dim: while to the east, the long curve of the land began to shine. Soon the whole wide world glowed blue, as if it was moulded out of sky and he was walking through the heavens.

The long, still, freezing night was almost over. The day was starting to arrive.

Cuthbert began to panic. What would happen when the sun rose? If it warmed him up, he might stop moving.

He might even start to melt. It was a dreadful thought, so dreadful that he suddenly halted in his tracks.

"What is it? What's the matter?" Ermine asked.

Cuthbert looked back, towards the little wood. Under the trees, it would stay cold and shady all day long, whether the sun shone or not. If he went back into the wood, he would not warm up. He would be safe.

But what about the lamb?

Cold Cuthbert stood quite still, and thought.

I have walked, and run, and played, he thought. I have made a friend, and seen the whole, wide, most extraordinary world. This lamb has not. Not yet.

And with that thought, he set off walking once again. He moved as fast as he could manage, before the sun should rise.

He walked into the village and down its crooked street in the dawn's blue twilight. Here the snow was packed hard underfoot: yet he made no more sound than a snowflake falling.

There was nobody about. But he could feel the heat of houses close on either side, sapping his strength. The warmth of the lamb's body, and his own mighty effort, made him weak and weary.

Now he saw the lemon gleam of morning fill the eastern sky; and he became afraid. Stumbling heavily, he nearly fell.

"Get up! Get up!" squeaked Ermine, running alongside him. "You're almost there!"

And with her darting down the street ahead of him and calling out encouragement, Cold Cuthbert struggled on towards his goal.

Chapter Five

Owen woke up with a start. He knew at once what day it was.

He crawled over his bed to check: yes, there it was, a red wool walking sock, full of interesting lumps and bumps!

Eagerly he reached inside and pulled out a chocolate reindeer. Biting off an antler, he stuffed it in his mouth while he unwrapped the next present - a tub of gel pens and a notebook.

Under that, he could feel something with wheels. But before he could investigate, there was a wail from Lily.

"Cold Cuthbert! Where's he gone? Who's stolen him?"

His presents forgotten, Owen ran to the window. Gasping at the sight of the empty field below, he ran helter-skelter down the stairs and out into the snow in his bare feet and pyjamas.

A moment later, Lily and Mum were out there with him. Lily was crying.

"I told you," said Mum, trying to comfort her, "he got up and walked away! Owen, go and put your boots on."

"Mum," whispered Owen, "what happened to the snowman? Did you hide him?"

She shook her head. "Somebody must have demolished him. Flattened him. That's the only answer I can think of."

It was the only answer that Owen could think of too. Once his boots were on, he inspected the ground where the snowman had stood, trying to work out which were his family's footprints and which might belong to a stranger.

It was impossible. He noticed lots of little prints made by some animal, and a series of strange, rounded dents in a line that led towards the wood; but they did not look like footprints.

None the less, somebody must have crept into the field and knocked Cold Cuthbert down - for snowmen did not walk. Even Lily could not be convinced that Cold Cuthbert had just strolled away.

Since the mystery could not be solved, after a while they went inside and spent a happier hour sharing out their gifts over their porridge, until it was time to go to church.

Owen didn't want to go to church; he wanted to stay at home and open presents. Dad didn't want to go; he said that he had too much work to do.

Lily didn't want to go: "Mr Gilpin doesn't like us," she complained.

"Not true," said Mum. "Mr Gilpin just gets tired. And he doesn't understand children very well, because he has no family."

"Nobody to give him presents?" Lily asked.

"No," said Mum. "We are lucky. Anyway, it's nice to go to church, to remember what Christmas is about."

So in the end Dad drove them down the snowy lane towards the village, and along the crooked street to the old church at the end.

Lily dragged her feet up the path. But once she was inside the church, she began to run.

There was a small crowd gathering around Saint Cuthbert's statue. And there was a big brown bundle at the statue's wooden feet.

"What on earth is all this bracken doing here?" demanded Mr Gilpin. He glared at Lily and at Owen.

Just at that moment, the parcel of bracken began to rustle. Then it bleated. A black nose stuck itself out and sneezed.

"It's a lamb!" cried Lily.

"A what?"

Mr Gilpin looked astounded. He reached into the bracken and picked up the lamb. At first it lay still in his arms; then it began to wriggle.

The minister's face had a very strange expression. Owen thought that he looked dazed and dazzled as he stared down at the lamb. He gently stroked it, and it tried to suck his finger.

Dad came hurrying over. "Born out of season," he said. "Amazing that it's still alive."

"What can we do for it?" asked Mr Gilpin.

"I'd better take it home right now and warm it up."

"Will it be all right?" The minister looked anxious.

"Oh, aye. It's cold, but with a bit of milk in its stomach, by a warm fire, it'll be as right as rain," Dad assured him. Carefully he took the lamb into his own strong hands.

"Dad! Is it one of ours?" Owen whispered.

"I don't know," said Dad, "but it doesn't matter."

"Let me know how it goes on!" begged Mr Gilpin.

"I will," Dad answered, and he carried the lamb out.

Mr Gilpin still looked dazed and dazzled. "But I don't understand. How did it get here?" he said. "Who brought it in?"

"Whoever it was," said Mum, "they left water all over the floor. Where do you keep your mop?"

Owen looked down. In the excitement, he had not noticed the pool of water that spread across the flagstones. A minute later, Mum was mopping it all up.

The mop hit something small and round that rolled across the floor. Owen ran to retrieve it.

It was a shiny, dark brown conker.

He spotted its partner; and then saw Lily holding out two shells. A huge smile spread across her face.

"It was him!" she said.

"What was who?" asked Mr Gilpin.

"It was Cuthbert! He brought in the lamb!"

"Cuthbert? Hmph," said Mr Gilpin, glancing at the statue.

"He walked," said Lily proudly, "because it was the coldest, stillest night of all the year!"

Mr Gilpin shook his head. But he did not frown or shout. Instead, he smiled. "It was certainly a very special night," he said. "Perhaps we could begin our service now?"

Mr Gilpin seemed to have chosen the chilliest, snowiest carols for the Christmas service.

"In the bleak midwinter,

Frosty wind made moan,

Earth stood hard as iron,

Water like a stone..."

Lily bellowed out the words with an enormous grin on her face. Then she paused to whisper to Owen.

"I bet Cold Cuthbert brought that lamb for Mr Gilpin because he never gets a present!"

Owen doubted this. Yet it occurred to him that Mr Gilpin might like to have the lamb, once it was well. He had looked so dazed and dazzled when he held it, as if he had never seen a new-born lamb before.

Now Mr Gilpin looked quite happy.

And Lily was happy, because Cold Cuthbert had walked.

Mum was happy, because she had persuaded them to come to church. Dad was happy, because he had gone home again with a lamb to look after.

And everybody else was happy because it was Christmas Day.

But Owen was not happy.

As he looked round the church, he was working it all out. He thought about what must have happened during that long night. He understood what Cold Cuthbert must have done.

He tried to guess how Cuthbert had felt, walking through the snow with the lamb; laying it down by the statue and then, in the warmth of the church, feeling himself grow weak - weaker even than the lamb that he had saved... then, unable to move any further, feeling himself begin to melt.

As Owen stared at the wet floor, the last trace of Cold Cuthbert, his eyes were wet too. His throat hurt so that he could not sing. He sniffed and looked up at the wooden statue.

While Saint Cuthbert did not look exactly happy, he did not look quite so severe as usual. Bracken suited him.

His eyes seemed to be fixed on the window, and Owen, sadly following his gaze, beheld a small stoat crouching on the windowsill. Although Saint Cuthbert did not care for crowds, possibly he did like animals. He seemed quite interested by the stoat, which was nibbling on a Brussels sprout.

That made Owen think of Christmas dinner, and his presents back at home, although they hardly seemed to matter now.

He wished he could give a present to Cold Cuthbert. The snowman had given the lamb its life. What could he give Cold Cuthbert?

Then he knew. He could give him his own story. There were twenty coloured gel pens back at home, just waiting to be used.

So while he listened to the joyful singing, Owen began to work out the first sentence he would write in his new notebook.

"He was the most wonderful snowman in the world..."

And Owen knew that it was true.

The End

Would you like another Christmas story?

Try Horace's Christmas Sleigh

or The Best Christmas Play Ever.